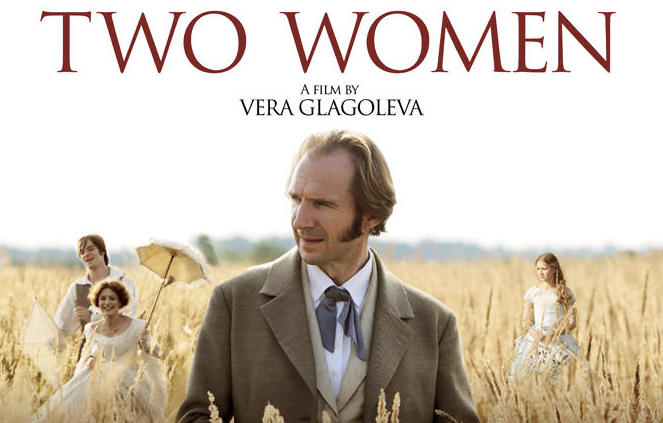

Two Women (2014)

In a cinematic era saturated with spectacle and speed, Vera Glagoleva’s Two Women (Две женщины) arrives like a whisper — delicate, intelligent, and devastating in its quietness. Based on Ivan Turgenev’s 1855 play A Month in the Country, this Russian-French co-production is less a straightforward love story than a meticulous study of emotional repression, unspoken longing, and social paralysis.

Released in 2014, Two Women brings together international talent, including Ralph Fiennes, who speaks fluent Russian in the role of the melancholic Rakitin, and the luminous Anna Vartanyan (Astrakhantseva) as the tormented lady of the estate, Natalya Petrovna. Set against the golden backdrop of 19th-century Russia, the film explores what happens when unexpressed desire festers — and becomes fatal.

📖 Plot: Still Waters Run Deep

The narrative takes place entirely on a country estate, during a stifling summer where heat is matched only by the emotional temperature inside the manor. Natalya Petrovna is an intelligent, passionate woman suffocated by convention and a loveless marriage to her older, pragmatic husband. When a young and idealistic tutor, Aleksei Belyaev (Nikita Volkov), arrives to educate her son, Natalya’s dormant emotions erupt into obsession.

The twist? Her teenage ward, Vera (Sylvia Testud), falls for the same tutor — and perhaps he for her. Rakitin, long in love with Natalya, watches from the sidelines with self-effacing sadness. What unfolds is a four-way emotional standoff where love is never fully reciprocated, but always painfully real.

This is not a story of seduction or betrayal in the conventional sense. Rather, it is about emotional dissonance — about how timing, class, and silence conspire to bury desire under layers of etiquette.

🎭 Acting: A Symphony of Glances and Stillness

Anna Vartanyan carries the film’s emotional weight with striking subtlety. Her performance as Natalya is a masterclass in restraint. She never raises her voice, but the longing in her eyes, the suppressed tremble of her hands, and the brittle edge in her conversations tell a fuller story than any confession. She is not written as a villain or seductress, but as a woman out of time — one whose intellect and feeling have no outlet.

Ralph Fiennes, as Rakitin, brings soul and sorrow. His command of Russian is admirable, but beyond language, he excels at conveying what it means to love without hope. His Rakitin is not weak — he’s noble in defeat, tragic in his loyalty. The chemistry between him and Vartanyan is not sensual, but spiritual. Their scenes together ache with what could never be.

Nikita Volkov and Sylvia Testud give youthful contrast — two characters who still believe in possibility, naïve but vibrant. The young tutor is not a rake, nor is Vera a mere rival. They are each caught in a net of someone else’s emotions — pawns in the emotional politics of the adult world.

🎨 Aesthetic: Literature in Motion

Visually, Two Women is ravishingly elegant. Director of photography Vladislav Opelyants crafts a visual palette reminiscent of oil paintings — warm earth tones, flowing linen, candlelit rooms, and sun-drenched meadows. Every frame is intentional. The estate is a prison wrapped in beauty: stunning but confining, lush but suffocating.

Lighting plays a critical role — twilight scenes capture moments of moral ambiguity; morning light often heralds regret or false hope. The stillness of the camera reflects the era’s cultural rigidity, making even the slightest gesture feel seismic.

Every cup of tea, every handwritten letter, every window gazed through becomes a symbol. It’s cinema for those who love the emotional weight of stillness — a story not driven by plot twists, but by internal tectonic shifts.

🎼 Sound & Score: The Echo of Elegance

The film’s soundtrack, composed by Sergey Banevich, enhances the atmosphere with delicate strings, sparse piano, and baroque instrumentation. But Glagoleva knows when to let silence speak louder. Many pivotal moments occur without music — letting words, or the lack thereof, echo louder than any orchestration.

The ambient sounds — creaking floorboards, rustling leaves, distant thunder — immerse us in a world where nature bears witness to human folly.

✍️ Fidelity to Turgenev

The screenplay remains close to Turgenev’s original text, preserving its lyrical, psychological richness. In doing so, it risks alienating modern viewers expecting drama to be louder or quicker. But those familiar with Russian literature will find it faithful in tone, character complexity, and moral ambiguity.

Turgenev’s themes — the waste of female intelligence in a patriarchal world, the dangers of emotional suppression, and the cruelty of mismatched affections — remain as relevant today as ever. The film’s feminism is subtle but present: Natalya is not condemned for her desire; she is tragic because her world denies her the right to desire at all.

💬 Reception and Legacy

Though it received a limited international release, Two Women was praised for its performances and visual beauty. It may not have garnered blockbuster attention, but for fans of literary cinema, it stands as a quiet triumph. It’s not flashy, but it lingers.

In an age of fast stories and louder emotions, Two Women reminds us of a lost art: the ache of restraint.

🎯 Final Verdict

Two Women is not just a period drama — it’s a meditation on emotional exile, beautifully rendered and exquisitely acted. For lovers of Chekhov, Turgenev, or Visconti, this film is an act of cinematic devotion. For those patient enough to listen, it rewards not with catharsis, but with a kind of mourning — for the things that could not be said, for the love that never found its place.

Rating: 8.8/10

“A refined, heartbreaking exploration of love unspoken and lives half-lived — painted with grace, silence, and unrelenting longing.”